»The later the day gets, the more immersed I am in my work.«

Interview with the artist Toulu Hassani

In 2016, Annette Stadler first encountered the works of Toulu Hassani at Art Basel, when a gallerist friend, with beaming eyes, presented one of her latest acquisitions. It was a piece by Toulu Hassani, which she had proudly added to her collection. Shortly thereafter, Annette and Rainer Stadler visited a comprehensive exhibition of Hassani's works at the Sprengel Museum in Hanover. Their fascination for her art, characterized by a tense balance between order and chaos, structure and dissolution, deepened even further.

In 2021, the Stadlers finally met the artist in person at Rüdiger Schöttle's gallery and acquired their first piece for their collection. Hassani's working method, based on intricate processes and an almost meditative attention to detail, exerts a strong attraction on the Stadlers and provides a fascinating contrast to many other works in their collection. In July 2024, Sophie Azzilonna spoke with Toulu Hassani about her art and the thoughts behind it.

Over the last months, you've had one exhibition after another. How do you manage to find time for your very elaborate works with all the organizational efforts and traveling?

It's actually not that easy. My works demand a relatively high level of attention from me. I deal with this situation by structuring my processes more than I did a few years ago. I set aside a fixed time for administrative tasks, usually in the morning. I sit down at my desk at home with a coffee and work through some tasks. When I'm traveling, I use the time on the train to answer emails and make plans. This helps me to concentrate fully on the artistic process in my studio. This work is extremely important for me and my process and needs to be shielded to a certain extent from organizational and planning considerations.

How do you prepare yourself for the meditative painting process? Do you have any specific rituals, times, or tools that you use?

I think when I arrive at the studio, I procrastinate a bit. I tidy up and organize tools and materials, mix colors, make notes or preliminary drawings. In this way, I create a calm and orderly environment in which nothing distracts me from painting. It takes a while for me to forget about external distractions and get into a deep state of concentration. I often listen to music when I start a new work or when I reach a challenging point in a painting. It releases thoughts and emotions in me that help me get into a flow. I like to incorporate these emotional states into my paintings. I love listening to podcasts when I'm busy with the more repetitive processes. The later the day gets, the more immersed I am in my work.

You often draw inspiration from scientific systems of order in your canvas works. What fascinates you about these systems?

I discovered that through the process of painting, I gradually approached these ideas, or perhaps I've always been there. The themes of order, system, and structure that occur in my works also happen in science in a very interesting way. I then began to look more intensively for analogies and overlaps between my paintings and scientific representations. In painting, similar processes and developments occur, although without being subject to equally strict rules or rather self-imposed rules. I believe it's less about inspiration between art and science, even though I consider that aspect important. I would like to take a step back on this question. For me, it's more about the motivation to pursue art or research. I think the same thing actually happens here. That's the essential idea for me. Both are attempts to connect with something outside of oneself. Both are approaches to the world with the aim, more or less, of identifying with something that is not oneself.

But in your order systems, you also consciously play with breaks...

I would rather say there's another level, that of intuitive and emotional decisions and image finding. Ultimately, what I do is very visual and can sometimes just be a purely visual experience without explanation.

entire wall in your exhibition "And So on to Infinity" at the Sauerland-Museum in Arnsberg. How did your approach differ compared to your canvas works?

The idea of the wall works goes back to a work that I showed for the first time in 2016 at the Sprengel Prize exhibition in Hanover. Back then, I experimented with the scan bed of a photocopier to create random gradients of brightness, which I later merged into a grid. The work "Minus Something" is, in my view, the technical starting point for these wall works. I then started using an airbrush, which I've been working with since 2020. In terms of content, I'm interested in the juxtaposition of the micro and macro levels in this type of work. The combination of small-format oil paintings with such wall works opens up a new space that makes the viewing and legibility of my works even more physical. For example, my gridded oil paintings can be read in a completely different way, as something endless, next to or on such a wall.

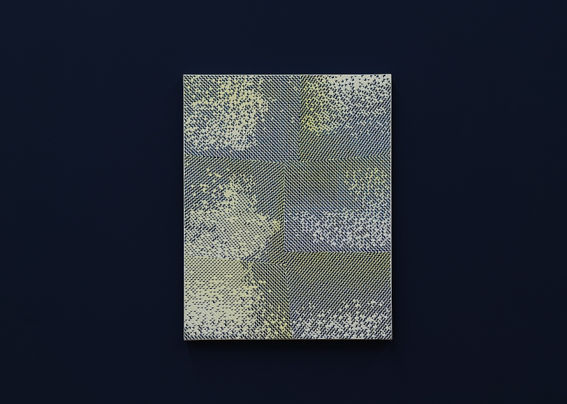

A new addition to our collection is the work 23:12 above horizon, 2023, which shows a section of the starry sky. Could you describe the work and the underlying idea in more detail?

The work 23:12 above horizon is part of an ongoing series. The title indicates the time the photograph used as a reference was taken. To be precise, details about the location and date of the photograph are missing. However, I am not interested in the most precise representation possible. The term "above horizon" comes from astronomy and, to me, it interestingly highlights that everything we observe, no matter how large or small, can only be described from our perspective. The night sky is mapped, and we know what can be seen around us, yet our own planet is in the way. The starry sky itself is something I associate with many things. At night, everything around us disappears into darkness, and the tiny stars in the distance magically attract my gaze. Thoughts seem freer and clearer at night than during the day, and at the same time, everyone is probably familiar with the thoughts of how small and insignificant we are as humans in the dimensions of the universe. Simultaneously, there is a great fascination for unsolved mysteries. Things and dimensions that surpass our imagination. The star paintings are perhaps an attempt to deliberately evoke such a moment.

Ten years ago, you were a scholarship holder in New York. You probably didn't get to see the starry sky that often there. Looking back, what influence did the city have on your work?

Even though the lights of the city almost always outshone the stars, I still remember many moments of looking at the sky. There were often opportunities to be on one of the rooftops and admire the expanse. The sunrises and sunsets were spectacular, especially in combination with the city. The influence of this stay on me is composed of many things. For me, the time spent and exchange with other artists were particularly important. I met most of them at the ISCP (International Studio & Curatorial Program). It was a very international environment. It was there that I particularly understood that an understanding of art draws on one's own socialization and has much more to do with learned experiences than I had previously realized. Apart from that, New York offers an incredible range of diverse input, which also puts the viewing and reflection of one's own work into new relations.

From 2023 to spring 2024, you taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. What do you enjoy about working with students, and what do you want to impart to them?

It's incredibly fun! I love engaging not only with my own art but also with the diverse thoughts and approaches of the students. This can sometimes be very challenging but is mainly enriching. At best, we encounter important questions and insights during work discussions or exhibition visits. It's important to me to create an atmosphere where we experience a lot together. This requires shared experiences beyond just work discussions. It's also particularly important to me that students work in the academy's studios. This way, they expose their works, in an unfinished, vulnerable state, to the scrutiny and critique of their fellow students. This kind of direct and sometimes brutal engagement was crucial for my artistic development. Above all, I want to convey the importance of finding and articulating one's own stance on art, one that engages with content rather than strategy and the art market. Additionally, I encourage openness, always questioning what is happening around you and how you relate to it. And of course, I want to push, encourage, and constructively critique the students.

Who has influenced or inspired you and your work?

To perhaps just name a few: David Lynch's ability to create a world that is completely unique and dreamlike. I stumbled upon his films when I was still too young and secretly watching TV. The dedication and passion of Werner Herzog have left a lasting impression on me. Paul Klee, Agnes Martin, and Vija Celmins are artists who repeatedly inspire me. In music, examples include Amen Dunes, Moses Sumney, or Tuxedomoon, extending to compositions by Philip Glass. The spectrum is very broad and I am always open to new and unfamiliar things.

Interview: Sophie Azzilonna

July 2024

Discover more artworks, exhibitions, and exclusive interviews with artists from the Stadler Collection.

with Gerold Miller